Category: home

*** NYTimes: This Conversation Will Change How You Think About Trauma

*** NYTimes.com: Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Spencer Ackerman

From The New York Times:

Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Spencer Ackerman

*** ‘The Standard American Diet Kills Us Slowly in Normal Times and Quickly in Covid Times’

‘The Standard American Diet Kills Us Slowly in Normal Times and Quickly in Covid Times’

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/09/opinion/sway-kara-swisher-michael-pollan.html?showTranscript=1

***** NYTimes.com: What if Humans Just Can’t Get Along Anymore?

From The New York Times:

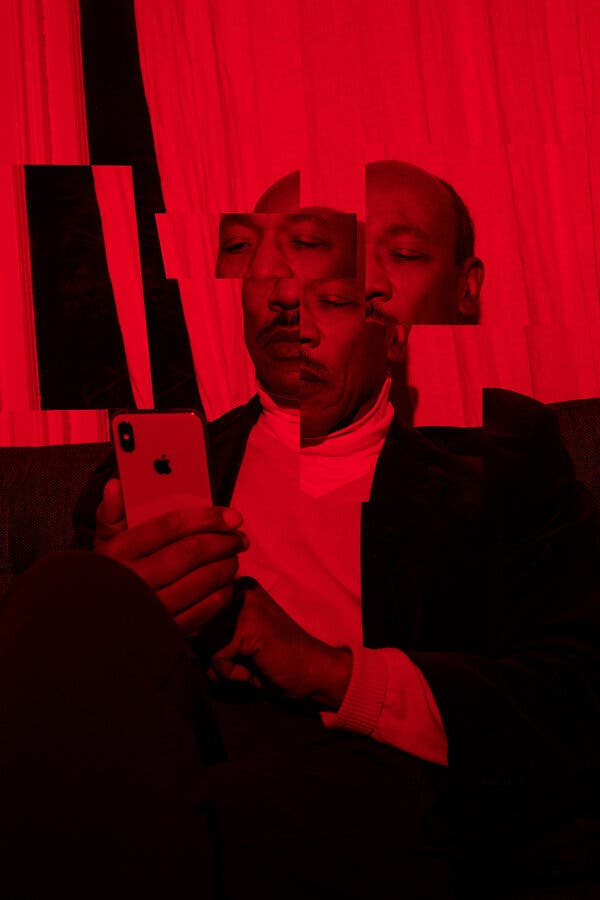

What if Humans Just Can’t Get Along Anymore?

Humanity’s greatest trick is working together. The internet has made that more difficult.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/04/opinion/technology-internet-cooperation.html?smid=em-share

FARHAD MANJOO

What if Humans Just Can’t Get Along Anymore?

Aug. 4, 2021

Credit…Aaron Wojack for The New York Times

·

·

·

Opinion Columnist

At the broadest level, human history is a story about cooperation. Individually, we big-brained, hairless primates are fairly ridiculous creatures, easy pickings for any dad-bod Simba roaming the plains. But get us together and we achieve dominion over land and sky.

Reluctantly, violently, often after exhausting every other possibility, people keep stumbling toward one another to get pretty much everything done. From the family to the village to the city, nation-state and global mega-corporation, cooperation and coordination among groups of increasing size and complexity is, for better or worse, how we all got to now.

But what if we’ve hit the limit of our capacity to get along? I don’t mean in the Mister Rogers way. I’m not talking about the tenor of our politics. My concern is more fundamental: Are we capable as a species of coordinating our actions at a scale necessary to address the most dire problems we face?

Because, I mean, look at us. With the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change, humanity is contending with global, collective threats. But for both, our response has been bogged down less by a lack of ideas or invention than by a failure to align our actions as groups, either within nations or as a world community. We had little trouble producing effective vaccines against this scourge in record time — but how much does that matter if we can’t get it to most of the world’s people and if even those who have access to the shots won’t bother?

Global failures of cooperation are, of course, nothing new; we did have those two world wars. But now we’re facing something perhaps even more worrying than nationalist enmity and territorial ambition. What if humanity’s capacity to cooperate has been undone by the very technology we thought would bring us all together?

The internet didn’t start the fire, but it’s undeniable that it has fostered a sour and fragmented global polity — an atmosphere of pervasive mistrust, corroding institutions and a collective retreat into the comforting bosom of confirmation bias. All of this has undermined our greatest trick: doing good things together.

It is true that each of us is affected differently by a changing climate and Covid-19, but with both, our fates are linked; what happens to each of us is tied up with the actions of others. Often the links are blurry. Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest could well affect the sea level in Florida, but it’s probably difficult to forge much common cause between poor farmers in Brazil and retirees in Boca Raton.

Sometimes, though, our fates are so obviously intertwined, you want to scream. Vaccines work best when most of us get them. Either we all patch up this sinking ship or we all go down together. But what if lots of passengers insist the ship’s not sinking and the repairs are a scam? Or the richest passengers stockpile the rations? And the captain doesn’t trust the navigator and the navigator keeps changing her mind and the passengers keep assaulting the crew?

I should say there is a good chance my take is too dreary. There has been a great deal of scholarship on how humans coordinate their actions in response to natural threats, and a great deal of it has echoed my pessimism — and been wrong. In 1968 the ecologist Garrett Hardin published a famous essay arguing that because people tend to maximize individual utility at the expense of collective good, our species was doomed to blindly exploit the world’s resources. He called this the “tragedy of the commons,” and in the following years he was among a group of intellectuals who advocated tough measures to avert the coming “population bomb,” among them curtailing the “freedom to breed.”

But Hardin was proved wrong both on the theory and on the prediction. (He was wrong about a lot of other things, too: He opposed immigration and global famine relief, and he maintained an interest in eugenics. The Southern Poverty Law Center says that white nationalism “unified his thought.”) The population bomb never went off. The world’s birthrate declined as the poorest people were lifted out of poverty. And as the pioneering political economist Elinor Ostrom showed over a lifetime of research, there are countless examples of people coming together to create rules and institutions to manage common resources. People aren’t profit-maximizing automatons; time and again, she found, we can make individual sacrifices in the interest of collective good.

Ostrom was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2009. In her prize lecture she wrote that “humans have a more complex motivational structure and more capability to solve social dilemmas” than rational-choice economists have given us credit for. The key to unlocking these capabilities, she said, was building the right institutions. Capitalist markets and nation-states had taken us only so far. Now, she suggested, we needed to imagine new kinds of groups that could improve how humans innovate, learn and adapt together to take on looming environmental challenges.

She died in 2012, so she did not witness what came next: the rise across much of the world of conspiratorial alternate realities and intense polarization that have hampered progress on so many global problems. As a species, we are still searching for the institutions Ostrom predicted we’d need to focus humanity’s collective power. I hope she was right that we are up to the task — but I can’t say I’m optimistic.

-home NYTimes: ‘Lean Into It. Lean Into the Culture War.’

NYTimes: Trumpism Without Borders

America is embedded in a world that is troubled by insidious parallel variants of the same structural problems — anti-immigrant fervor, political tribalism, racism, ethnic tension, authoritarianism and inequality — that led to a right-wing takeover of the federal government by Donald Trump.

The peculiarly American characteristics of the Trump years have blinded us to the spread of this radical disorder worldwide — even as some prescient scholars and analysts have seen the connections all along and have been trying to make the public aware of them.

NYTimes: Speaking Truth to Both the Right and the Left

*** I asked a wise man….

*** Opinion Today: Your house doesn’t know your racial identity, right?

Keywords: home ownership race identity whiteness wealth value declines

Your neighbors and potential neighbors do.

|

||||||||||||||||||||